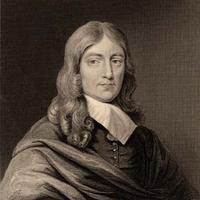

01c. Life of John Milton by Sir Richard C. Jebb. Part 3/4.

The summer of 1639 (July) found Milton back in England. Immediately after his return he wrote the Epitaphium Damonis, the beautiful elegy in which he lamented the death of his school friend, Diodati. Lycidas was the last of the English lyrics: the Epitaphium, which should be studied in close connection with Lycidas, the last of the long Latin poems. Thenceforth, for a long spell, the rest was silence, so far as concerned poetry. The period which for all men represents the strength and maturity of manhood, which in the cases of other poets produces the best and most characteristic work, is with Milton a blank. In twenty years he composed no more than a bare handful of Sonnets, and even some of these are infected by the taint of political animus. Other interests claimed him—the question of Church-reform, education, marriage, and, above all, politics.

Milton's first treatise upon the government of the Church (Of Reformation in England) appeared in 1641. Others followed in quick succession. The abolition of Episcopacy was the watchword of the enemies of the Anglican Church—the delenda est Carthago cry of Puritanism, and no one enforced the point with greater eloquence than Milton. During 1641 and 1642 he wrote five pamphlets on the subject. Meanwhile he was studying the principles of education. On his return from Italy he had undertaken the training of his nephews. This led to consideration of the best educational methods; and in the Tractate of Education, 1644, Milton assumed the part of educational theorist. In the previous year, May, 1643, he married. The marriage proved unfortunate. Its immediate outcome was the pamphlets on divorce. Clearly he had little leisure for literature proper.

The finest of Milton's prose works, Areopagitica, a plea for the free expression of opinion, was published in 1644. In 1645 appeared the first collection of his poems. In 1649 his advocacy of the anti-royalist cause was recognised by the offer of a post under the newly appointed Council of State. His bold vindication of the trial of Charles I, The Tenure of Kings, had appeared earlier in the same year. Milton accepted the offer, becoming Latin Secretary to the Committee of Foreign Affairs. There was nothing distasteful about his duties. He drew up the despatches to foreign governments, translated state papers, and served as interpreter to foreign envoys. Had his duties stopped here his acceptance of the post would, I think, have proved an unqualified gain. It brought him into contact with the first men in the state, gave him a practical insight into the working of national affairs and the motives of human action; in a word, furnished him with that experience of life which is essential to all poets who aspire to be something more than “the idle singers of an empty day.” But unfortunately the secretaryship entailed the necessity of defending at every turn the past course of the revolution and the present policy of the Council. Milton, in fact, held a perpetual brief as advocate for his party. Hence the endless and unedifying controversies into which he drifted; controversies which wasted the most precious years of his life, warped, as some critics think, his nature, and eventually cost him his eyesight.

Between 1649 and 1660 Milton produced no less than eleven pamphlets. Several of these arose out of the publication of the famous Eikon Basilike. The book was printed in 1649 and created so extraordinary a sensation that Milton was asked to reply to it; and did so with Eikonoklastes. Controversy of this barren type has the inherent disadvantage that once started it may never end. The Royalists commissioned the Leyden professor, Salmasius, to prepare a counterblast, the Defensio Regia, and this in turn was met by Milton's Pro Populo Anglicano Defensio, 1651, over the preparation of which he lost what little power of eyesight remained. Salmasius retorted, and died before his second farrago of scurrilities was issued: Milton was bound to answer, and the Defensio Secunda appeared in 1654. Neither of the combatants gained anything by the dispute; while the subsequent development of the controversy in which Milton crushed the Amsterdam pastor and professor, Morus, goes far to prove the contention of Mr Mark Pattison, that it was an evil day when the poet left his study at Horton to do battle for the Commonwealth amid the vulgar brawls of the market-place:

Not here, O Apollo,

Were haunts meet for thee.

Fortunately this poetic interregnum in Milton's life was not destined to last much longer. The Restoration came, a blessing in disguise, and in 1660 the ruin of Milton's political party and of his personal hopes, the absolute overthrow of the cause for which he had fought for twenty years, left him free. The author of Lycidas could once more become a poet.

Much has been written upon this second period, 1639—60. We saw what parting of the ways confronted Milton on his return from Italy. Did he choose aright? Should he have continued upon the path of learned leisure? There are writers who argue that Milton made a mistake. A poet, they say, should keep clear of political strife fierce controversy can benefit no man who touches pitch must expect to be, certainly will be, defiled: Milton sacrificed twenty of the best years of his life, doing work which an underling could have done and which was not worth doing: another Comus might have been written, a loftier Lycidas: that literature should be the poorer by the absence of these possible masterpieces, that the second greatest genius which England has produced should in a way be the “inheritor of unfulfilled renown,” is and must be a thing entirely and terribly deplorable. This is the view of the purely literary critic.

There remains the other side of the question. It may fairly be contended that had Milton elected in 1639 to live the scholar's life apart from “the action of men,” Paradise Lost, as we have it, or Samson Agonistes could never have been written. Knowledge of life and human nature, insight into the problems of men's motives and emotions, grasp of the broader issues of the human tragedy, all these were essential to the author of an epic poem; they could only be obtained through commerce with the world; they would have remained beyond the reach of a recluse. Dryden complained that Milton saw nature through the spectacles of books: we might have had to complain that he saw men through the same medium. Fortunately it is not so: and it is not so because at the age of thirty-two he threw in his fortunes with those of his country; like the diver in Schiller's ballad he took the plunge which was to cost him so dear. The mere man of letters will never move the world. Æschylus fought at Marathon: Shakespeare was practical to the tips of his fingers; a better business man than Goethe there was not within a radius of a hundred miles of Weimar.